Three Picture Andes Theme Art Frame for Dinnig Room

| The Heart of the Andes | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Frederic Edwin Church |

| Year | 1859 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 167.9 cm × 302.9 cm (66.1 in × 119.3 in) |

| Location | Metropolitan Museum of Art |

The Heart of the Andes is a large oil-on-canvas landscape painting by the American artist Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900).

At more five anxiety (1.7 metres) loftier and nearly x feet (iii metres) wide, it depicts an idealized landscape in the South American Andes, where Church traveled on two occasions. Its exhibition in 1859 was a sensation, establishing Church equally the foremost landscape painter in the United States.[1]

The painting has been in the collection of New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art since 1909, and is among Church building'due south virtually renowned works.

Background [edit]

In 1853 and 1857, Church traveled in Ecuador and Colombia, financed by man of affairs Cyrus W Field, who wished to use Church'southward paintings to lure investors to his S American ventures. Church was inspired by the Prussian naturalist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt, and his 1845 treatise Kosmos. Humboldt was among the final of the great scientific generalists, and his fame became like to that of Albert Einstein a century subsequently.[2] In the 2d volume of Kosmos, Humboldt described the influence of mural painting on the study of the natural globe—holding that art is among the highest expressions of the love of nature[3]—and challenging artists to portray the "physiognomy" of the mural.[2] [iv] Church retraced Humboldt'due south travels in S America.

Description and influences [edit]

The Eye of the Andes is a composite of the S American topography observed during his travels. At the center right of the mural is a shimmering puddle served by a waterfall. The snow-capped Mount Chimborazo of Ecuador appears in the distance; the viewer's eye is led to it by the darker, closer slopes that decline from right to left. The evidence of human presence is shown past the lightly worn path, a hamlet and church lying in the central plain, and closer to the foreground, two locals are seen before a cross. The church, a trademark item in Church's paintings, is Catholic and Spanish-colonial, and seemingly inaccessible from the viewer's location. Church's signature appears cutting into the bawl of the highlighted foreground tree at left. The play of light on his signature has been interpreted as the creative person'due south argument of man's ability to tame nature—yet the tree appears in poor health compared to the vivid jungle surrounding it.[v]

Church'south landscape conformed to the aesthetic principles of the picturesque, as propounded by the British theorist William Gilpin, which began with a conscientious ascertainment of nature enhanced by particular notions about limerick and harmony. The juxtaposition of shine and irregular forms was an of import principle, and is represented in The Heart of the Andes past the rounded hills and pool of water on the i hand, and by the contrasting jagged mountains and crude trees on the other.[6]

The theory of British critic John Ruskin was also an important influence on Church. Ruskin's Mod Painters was a five-book treatise on art that was, co-ordinate to American creative person Worthington Whittredge, "in every landscape painter's hand" by mid-century.[seven] Ruskin emphasized the shut observation of nature, and he viewed art, morality, and the natural world as spiritually unified. Post-obit this theme, the painting displays the mural in detail at all scales, from the intricate leafage, birds, and collywobbles in the foreground to the extensive portrayal of the natural environments studied past Church. The presence of the cross suggests the peaceful coexistence of religion with the landscape.[1]

Exhibition [edit]

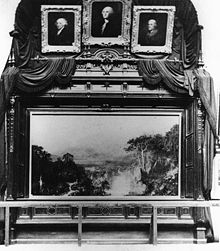

In that location is no photographic record of the 1859 exhibition of The Heart of the Andes; its exhibition in 1864 is pictured. The overhanging portraits and handrails were added for its inclusion in the fine art gallery at New York'south Metropolitan Germ-free Fair.

The Heart of the Andes was first exhibited publicly between April 29 and May 23, 1859 at New York's Tenth Street Studio Building, the city'due south commencement studio building designed for artists.[eight] Church had exhibited unmarried paintings previously, such as Niagara (1857), to much success. The outcome attracted an unprecedented turnout for a unmarried-painting exhibition in the U.s.a.: more than 12,000 people paid an admission fee of twenty-five cents to view the painting. Even on the final day of the showing, patrons waited in line for hours to enter the Exhibition Room.[8]

In that location is no record of the advent or arrangement of the Studio Building showroom. Information technology has been widely claimed, although probably falsely, that the room was decorated with palm fronds and that gaslights with silver reflectors were used to illuminate the painting.[8] More sure is that the painting'south casement-window–like "frame" had a breadth of fourteen feet and a top of nigh xiii, which further imposed the painting upon the viewer. Information technology was likely made of brown chestnut, a departure from the prevailing gilt frame. The base of operations of the building stood on the basis, ensuring that the landscape's horizon would exist displayed at the viewer'southward middle level. Drawn defunction were fitted, creating the sense of a view out a window. A skylight directed at the canvas heightened the perception that the painting was illuminated from inside, as did the night fabrics draped on the studio walls to absorb lite. Opera spectacles were provided to patrons to allow exam of the landscape's details, and may have been necessary to satisfactorily view the painting at all, given the crowding in the exhibition room.[8]

Church building's canvas had a strong result on its viewers; a contemporary witness wrote: "women felt faint. Both men and women succumb[ed] to the boundless combination of terror and vertigo that they recognize[d] equally the sublime. Many of them will later on describe a sensation of becoming immersed in, or absorbed by, this painting, whose dimensions, presentation, and subject affair speak of the divine ability of nature."[6]

Accompanying the access were two pamphlets nigh the painting: Theodore Winthrop'southward A Companion to The Centre of the Andes and the Reverend Louis Legrand Noble's Church building'southward Film, The Eye of the Andes. In the manner of travel guides, the booklets provided a bout of the painting's varied topography. An excerpt from Noble reads:

Imagine yourself, belatedly in the afternoon with the sunday behind you, to be travelling upward the valley forth the bank of a river, at an elevation above the hot country of some 5 or six thousand feet. At the point to which you have ascended, heavily-wooded mountains close in on either mitt, (non visible in the picture – only the human foot of each bulging into view,) richly clothed with trees and all the appendage of the forest, with the river flowing betwixt them. ... Conspicuous on the contrary side of the river is the road leading into the country in a higher place, a wild bridle-path in the brightest sunshine, winding up into, and losing itself in the thick shady woods. The foreground ... forms of itself a scene of unrivalled ability and brilliancy, ...[8]

Church building wanted Humboldt, his intellectual mentor, to see his masterpiece. Shut to the end of the first exhibition, on May 9, 1859 he wrote of this desire to American poet Bayard Taylor:

The "Andes" will probably be on its way to Europe before your return to the City ... [The] principal motive in taking the motion-picture show to Berlin is to have the satisfaction of placing before Humboldt a transcript of the scenery which delighted his optics sixty years agone—and which he had pronounced to be the finest in the globe.[3]

Humboldt, however, died on May half-dozen and then the planned shipment to Europe did not occur. This disappointed Church, but he would presently encounter his time to come wife Isabel at the New York exhibition.[nine] Later in 1859, the painting was exhibited in London (July 4 – c. Baronial fourteen), where it met with similar popularity. Returning to New York Metropolis, information technology was exhibited over again from October x to December 5. In the next few years, showings occurred in Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Cincinnati, Chicago, and St. Louis. An 1864 exhibition at the Metropolitan Sanitary Fair at New York'due south Spousal relationship Foursquare is meliorate documented than the original, with photographs extant.

Reproduction [edit]

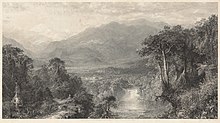

The 1862 engraving by Charles Mean solar day & Son. 34.4 ten 63.two cm

While the painting was in London, Church's amanuensis arranged to take an engraving of it fabricated by Charles Solar day & Son, which would allow for broad distribution of reproductions and hence more income. Sometime during this menstruum a watercolor copy of The Eye of the Andes was made. It is not certain who painted the re-create, merely Church very likely is non the creative person; the engraver Richard Woodman or one of his sons has been proposed. The watercolor is now presumed to have originated in Great britain and been fabricated for the use of the engraver, William Forrest of Edinburgh. The watercolor is at present in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.[x] [11]

Reception and legacy [edit]

The painting was widely acclaimed. Poetry was written in its award, and a composer, George William Warren, defended a piece to information technology in 1863. Mark Twain described the painting to his brother Orion Clemens in a letter of 1860:[12]

I have just returned from a visit to the most wonderfully beautiful painting which this city has e'er seen—Church'due south 'Heart of the Andes' ... I have seen information technology several times, but it is always a new picture—totally new—you seem to see nothing the 2nd time which y'all saw the showtime. We took the opera glass, and examined its beauties minutely, for the naked eye cannot discern the lilliputian wayside flowers, and soft shadows and patches of sunshine, and half-hidden bunches of grass and jets of h2o which form some of its well-nigh enchanting features. At that place is no slurring of perspective effect virtually it—the most distant—the minutest object in it has a marked and distinct personality—and then that y'all may count the very leaves on the trees. When you start see the tame, ordinary-looking pic, your first impulse is to turn your back upon information technology, and say "Humbug"—but your third visit will find your brain gasping and straining with futile efforts to take all the wonder in—and appreciate it in its fulness and sympathize how such a miracle could have been conceived and executed by human encephalon and human hands. You will never get tired of looking at the moving-picture show, but your reflections—your efforts to grasp an intelligible Something—you hardly know what—will abound so painful that you will have to go abroad from the affair, in guild to obtain relief. You lot may find relief, simply you cannot banish the pic—it remains with y'all all the same. It is in my mind now—and the smallest characteristic could not exist removed without my detecting it.[13]

The New York Times described the painting's "harmony of design" and "chaos of chords or colors gradually rises upon the enchanted heed a rich and orderly creation, full of familiar objects, still wholly new in its combinations and its significance."[14]

Church eventually sold the work to William Tilden Blodgett for $x,000—at that fourth dimension the highest toll paid for a piece of work by a living American artist. Moreover, Church reserved the right to re-sell the painting should he receive an offer of at least $20,000. (American landscapist Albert Bierstadt surpassed both prices when he sold The Rocky Mountains, Lander's Pinnacle for $25,000[15] in 1865.) Blodgett held the painting until his death in 1875.[16] Information technology was acquired past Margaret Worcester Dows, widow of grain merchant David Dows, and bequeathed to the Metropolitan Museum of Art upon her death in February 1909.[17] In 1993, the museum held an exhibition that attempted to reproduce the conditions of the 1859 showroom.

Contempo descriptions place it within mod thematic discourse, including the tension between art and science, and American territorial expansion. The split between the humanities and the scientific worldview was nascent in 1859: Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species was published afterward in the same yr as Church's painting.[3]

References [edit]

- Notes

- ^ a b Craven, Wayne (2002). American Fine art: History and Civilisation. McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. 207–209. ISBN978-0-07-141524-8.

- ^ a b Gardner, Albert Ten Eyck (October 1945). "Scientific Sources of the Full-Length Landscape: 1850". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. New Series. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 4 (ii): 59–65. doi:10.2307/3257164. JSTOR 3257164.

- ^ a b c Gould, Stephen Jay. "Church, Humboldt, and Darwin: The Tension and Harmony of Art and Scientific discipline." Latin American Popular Civilization: An Introduction. Rowman & Littlefield: 2000. ISBN 0-8420-2711-4; pp. 27–42.

- ^ Büttner, Nils (2006). Mural Painting: A History. trans. Russell Stockman. New York: Abbeville Press Publishers. pp. 283–285. ISBN978-0-7892-0902-3.

- ^ Sachs, pp. 99–100

- ^ a b Poole, Deborah. "Mural and the Royal Subject field: U.Due south. Images of the Andes, 1859–1930." Close Encounters of Empire: Writing the Cultural History of U.S.-Latin American Relations. Duke Academy Press: 1998. ISBN 0-8223-2099-one; pp. 107–138.

- ^ Wagner, Virginia L.; Ruskin, John (Summertime–Fall 1988). "John Ruskin and Artistical Geology in America". Winterthur Portfolio. 23 (2/3): 151–167. doi:10.1086/496374.

- ^ a b c d e Avery (1986)

- ^ Howat, 88

- ^ Carr, Gerald 50. (1982). "American Fine art in U.k.: The National Gallery Watercolor of 'The Centre of the Andes'". Studies in the History of Fine art. 12: 81–100. JSTOR 42617951.

- ^ "The Heart of the Andes". National Gallery of Art . Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- ^ Twain, Mark (1929). Mark Twain's Letters, Vol. 2. Jazzybee Verlag Jurgen Beck. pp. 15–xvi. ISBN9783849674632.

- ^ Avery (1993), 43–44

- ^ Quoted in Sachs, pp. 99—100

- ^ Huntington, David C. (1966). The Landscapes of Frederic Edwin Church building: Vision of an American Era. George Braziller. p. 88. LCCN 66-16675.

- ^ Howat, 89

- ^ The New York Times, February 3, 1909

- Sources

- Avery, Kevin J. (Winter 1986). "The Heart of the Andes Exhibited: Frederic E. Church's Window on the Equatorial Earth". American Fine art Journal. Kennedy Galleries, Inc. 18 (1): 52–72. doi:10.2307/1594457. JSTOR 1594457.

- Avery, Kevin J. (1993). Church's Dandy Moving picture, the Eye of the Andes. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN9780810964518.

- Sachs, Aaron (2007). The Humboldt Current: A European Explorer and His American Disciples. Oxford University Printing. ISBN 0-nineteen-921519-7

External links [edit]

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art offers a zoomable view of the painting and photographs of the installation.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Heart_of_the_Andes

0 Response to "Three Picture Andes Theme Art Frame for Dinnig Room"

Post a Comment